No products in the cart.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda is the oldest surviving complete medical system in the world. Its origins date back almost 5,000 years, deriving from its ancient Sanskrit roots – “ayus” (life) and “ved” (knowledge) – and offer a rich and comprehensive view of healthy living. Until it was explained and practiced by the same spiritual rishis who laid the foundations of Vedic civilization in India by arranging the fundamentals of life into proper systems.

Therefore, the main source of knowledge in this area remains the Vedas, the divine books of knowledge that they presented, and more specifically the fourth of the series, the Atharvaveda, which dates back to around 1000 BC. Of the few other treatises on Ayurveda that have survived from around the same time, the best known are the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita, which focus on internal medicine and surgery. The Astanga Hridajam is a more concise compilation of earlier texts that was composed about a thousand years ago. These among them form the greater part of the knowledge base about Ayurveda as it is practiced today.

The art of Ayurveda spread in the 6th century BC to Tibet, China, Mongolia, Korea and Sri Lanka, brought by Buddhist monks traveling to these countries. Although not much of it survives in its original form.

No philosophy has had a greater influence on Ayurveda than Sankhaya’s philosophy of creation and manifestation. Which professes that behind all creation is a state of pure existence or awareness that is beyond time and space, without beginning or end and without attributes. In pure existence, the desire to experience oneself arises, which results in imbalance and causes the primal physical energy to manifest. And the two join forces to bring the “dance of creation” to life.

Samhita

Kashyap Samhitā

Kashyap Samhitā (Dévanagari कश्यप स्महिता, also Kashyapa, Kasyap, Kasyapa), also known as the Vriddha Jivakiya Tantra is a treatise on Ayurveda attributed to the sage Kashyapa.

The text is often cited as one of the earliest treatises on Indian medicine, alongside works such as the Sushruta Samhita, Charaka Samhita, Bhela Samhita, and Harita Samhita. It depends on the work of ayuvedic practitioner Charaka.

In the current practice of Ayurveda, it is often consulted in the fields of Ayurvedic pediatrics, gynecology and obstetrics. It is also part of the Ayurvedic teaching curriculum, especially in Kaumarabhritya Balaroga. The treatise was translated into Chinese during the Middle Ages.

The Kashyap Samhita contains 200 chapters.

- Sutra sthan, of 30 chapters

- Nidan sthan, of 8 chapters

- Vimana sthan, of 8 chapters

- Shareer sthan, of 8 chapters

- Indriya sthan, of 12 chapters,

- Chikitsa sthan, of 30 chapters,

- Siddhi sthan, of 12 chapters

- Kalpa sthan, of 12 chapters

- Khil Bhag, of 80 chapters.

Bhela Samhita

Bhela was one of Atreya’s six students along with Agnivesha. He is said to have composed a treatise called Bhela Samhita. This could not be traced for many centuries, but in 1880 his palm-leaf manuscript, composed in Sanskrit but written in the Telugu script, was found in the palace library at Tanjore. This manuscript, written around 1650, is full of errors and some of them have been disfigured beyond recognition. But whatever has survived bears witness to the same ancient tradition as the Charaka Samhita. It also has eight divisions like the Charaka, and each section ends, “Thus spake Atreya,” as in the Charaka Samhita. The Bhela Samhita basically confirms what the Charaka Samhita says. Sometimes it differs from him in some details.

Nava Nitaka

The practice of Ayurvedic medicine entered a new phase when instead of samhitas on medicine and surgery, compendiums of recipes for various diseases began to appear. The first of such treatises which we now have with us is the Nava Nitaka. This manuscript was discovered by a man from Kuchar, an oasis of East Turkestan in Central Asia, on a caravan trip to China. This route was used by Buddhist monks from India traveling to distant places. This man was digging in hopes of finding some treasure in an area that is supposed to contain an underground city. He found no fortune, but discovered a manuscript which was bought for a small sum by L.H. Bower, who had gone there on a private mission from the Government of India. This manuscript was given to J. Waterhouse, then President of the Asiatic Society. It was deciphered and published by A.F. Hoernl, who spent 21 years studying it. The manuscript was then sold to the Bodlein Library in Oxford.

The Nava Nitaka manuscript by name or content has been mentioned by various authors between the tenth and sixteenth centuries. After that no one mentioned this manuscript until it was rediscovered. The present manuscript consists of very defective Sanskrit mixed with Prakrit. It was written in the fourth or fifth century Gupta script. The material on which it is written is birch bark, cut into oblong foils like the palm leaves of South and West India. The content suggests a Buddhist influence in its composition.

According to Hoernle, the entire manuscript consists of no fewer than five distinct parts. The author quotes from Charaka and Susruta and Bhela Samhita. The name ‘Nava-Nitaka’, meaning butter, indicates the method of its composition; just as small amounts of butter are extracted from milk, so this work contains basic formulas extracted from other larger works. According to one scholar, the author of the Nava-Nitaka was Navanita.

The Nava-Nitaka for the first time details the use of garlic in various diseases such as consumption (rajya yakshma) and scrofulous glands in the neck. Tied with thread, it was also hung on the door; this was to prevent the spread of infectious diseases such as smallpox. Garlic was recommended to be used in winter and spring.

Harita Samhita

The Harita Samhita is one of the classic works on Ayurvedic medicine, written between the 6th and 7th centuries AD. This book is written in conversation module and the conversation was between Maharshi Atreya and Acharya Harita. Acharya Harita proposed his own new concepts in his texts. This text is divided into six parts i.e. Prathamasthana, Dwitiyasthana, Chikitsasthana, Sutrasthana, Kalpasthana, Sharirasthana. Harita Samhita can be included under Dravyaguna Shastra. In this work the concepts of Acharya Harita have been critically analyzed and systematically elaborated. Another scope of study is to critically analyze the work of Acharya Harita and explore his views on Ayurvedic scholars.

Charaka Samhita

The Charaka Samhita (IAST: Caraka-Saṃhitā, “Compendium of Charaka”) is a Sanskrit text on Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine). Along with the Sushruta Samhita, it is one of the two foundational texts of the discipline that have survived from ancient India. It is one of the three works that make up the Brhat Trayi.

The text is based on the Agnivesha Samhita, an encyclopedic medical compendium from the eighth century BC by Agniveśa. It was revised by Charaka between 100 BCE and 200 CE and renamed Charaka Samhitā.

The text, dating from before the 2nd century AD, consists of eight books and one hundred and twenty chapters. It describes ancient theories about the human body, etiology, symptomology and therapy of a wide range of diseases. The Charaka Samhita also contains sections on the importance of diet, hygiene, prevention, medical education, and the teamwork of doctor, nurse, and patient necessary for recovery.

The Charaka Samhita states that the contents of the book were first taught by Atreya and then codified by Agniveśa, revised by Charaka (a Kashmiri by origin) and the manuscripts that survive into the modern era are based on the manuscript completed by Dṛḍhabala. Dṛḍhabala stated in the Charaka Samhita that he had to write one-third of the book himself because that part was lost, and that he also rewrote the last part of the book.

Based on textual analysis and the literal meaning of the Sanskrit word charak, Chattopadhyay speculated that charak does not refer to one person but to multiple people. Vishwakarma and Goswami state that the text exists in many versions, with some versions missing entire chapters.

The extant text has eight sthāna (books), totalling 120 chapters. The text includes a table of contents embedded in its verses, stating the names and describing the nature of the eight books, followed by a listing of the 120 chapters.These eight books are:

- Sutra Sthana (General principles) – 30 chapters deal with general principles, philosophy, definitions, prevention through healthy living, and the goals of the text. It is divided into quadruplets of 7, making it 28 with 2 concluding chapters.

- Nidana Sthana (Pathology) – 8 chapters on causes of diseases.

- Vimana Sthana (Specific determination) 8 chapters contain training of a physician, ethics of medical practice, pathology, diet and nourishment, taste of medicines.

- Śarira Sthana (Anatomy) – 8 chapters describe embryology & anatomy of a human body (with a section on other living beings).

- Indriya Sthana (Sensory organ based prognosis) – 12 chapters elaborate on diagnosis & prognosis, mostly based on sensory response of the patient.

- Cikitsa Sthana (Therapeutics) – 30 chapters deal with medicines and treatment of diseases.

- Kalpa Sthana (Pharmaceutics and toxicology) – 12 chapters describe pharmacy, the preparation and dosage of medicine, signs of their abuse, and dealing with poisons.

- Siddhi Sthana (Success in treatment) – 12 chapters describe signs of cure, hygiene and healthier living.

Seventeen chapters of Cikitsā sthāna and complete Kalpa sthāna and Siddhi sthāna were added later by Dṛḍhabala. The text starts with Sūtra sthāna which deals with fundamentals and basic principles of Ayurveda practice. Unique scientific contributions credited to the Caraka Saṃhitā include:

- a rational approach to the causation and cure of disease

- introduction of objective methods of clinical examination

Sushruta Samhita

The Sushruta Samhita (सुश्रुतसंहिता, IAST: Suśrutasaṃhitā, literally “Suśruta’s Compendium.”) is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, one of the most important subjects in this world. The Compendium of Suśruta is one of the foundational texts of Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine), alongside the Charaka-Saṃhita, the Bheḷa-Saṃhita and the medical parts of the Bower Manuscript. It is one of two basic Hindu texts on the medical profession that have survived from ancient India.

The Suśrutasaṃhitā is of great historical importance as it contains historically unique chapters describing surgical training, instruments and procedures that still guide the modern science of surgery. One of the oldest palm-leaf manuscripts of the Sushruta Samhita is preserved in the Kaiser Library in Nepal.

More than a century ago, the scholar Rudolf Hoernle (1841–1918) suggested that since the author of the Satapatha Brahmana, a Vedic text of the mid-first millennium BCE, knew about Sushruta’s doctrines, Sushruta’s doctrines should be dated based on the date of composition of the Satapatha Brahman. The date of the composition of the Brahmana itself is unclear, Hoernle added, estimating it at about the 6th century BC. Hoernle’s date of 600 BCE for the Suśrutasaṃhitā continues to be widely and uncritically cited despite much intervening scholarship. Dozens of scholars subsequently published opinions on the date of the work, and these many opinions were summarized by Meulenbeld in his History of Indian Medical Literature. Boslaugh dates the currently extant text to the 6th century CE.

A central problem with the chronology is the fact that the Suśrutasaṃhitā is the work of several hands. Internal tradition recorded in manuscript colophons and medieval commentators makes it clear that the old version of the Suśrutasaṃhita consisted of sections 1-5, with a sixth section added by a later author. However, the oldest manuscripts of the work that we have already contain the sixth section.

Sushruta (Dévanagari सुश्रुत, adjective meaning “illustrious”) is listed as the author in the text, who is presented in later manuscripts and printed editions as recounting the teachings of his guru Divodāsa. A person of this name is said in early texts such as the Buddhist Jatakas to have been a physician who taught at a school in Kashi (Varanasi) concurrently with another medical school at Taxila (on the Jhelum River), sometime between 1200 BCE and 600 BCE. The earliest known mention of the name Sushruta firmly associated with the Suśrutasaṃhitā tradition is in the Bower Manuscript (4th or 5th century CE), where Sushruta is listed as one of ten sages residing in the Himalayas.

Rao suggested in 1985 that the author of the original “layer” was “the elder Sushruta” (Vrddha Sushruta), although this name does not appear anywhere in early Sanskrit literature. The text, Rao states, was redacted centuries later “by another Sushruta, then by Nagarjuna, and then the Uttara-tantra was added as a supplement. It is generally accepted by scholars that several ancient authors called “Suśruta” contributed to it. text.

One of the oldest palm-leaf manuscripts of the Sushruta Samhita was discovered in Nepal. It is held in the Kaiser Library in Nepal as manuscript KL–699, a digital copy of which has been archived by the Nepal-German Manuscript Conservation Project (NGMCP C 80/7). The partially damaged manuscript consists of 152 double-sided folios with 6 to 8 lines in transitional Gupta script. The manuscript has been verifiably dated as completed by the scribe on Sunday 13 April 878 AD (Manadeva Samvat 301).

Much of the scholarship on the Suśruta-saṃhita is based on editions of the text that were published during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This includes the important edition of Vaidya Yādavaśarmana Trivikramātmaja Ācārya, which also contains the commentary of the scholar Dalhaṇa.

The printed editions are based on a small subset of the surviving manuscripts that were available at the major publishing centers in Bombay, Calcutta, and elsewhere when the editions were being prepared—sometimes as few as three or four manuscripts. However, these do not adequately represent the large number of manuscript versions of the Suśruta-saṃhita that have survived into the modern era. Taken together, all printed versions of the Suśrutasaṃhita are based on no more than ten percent of the more than 230 manuscripts of the work that exist today. These manuscripts exist today in libraries in India and abroad. More than two hundred manuscripts of the work exist, and a critical edition of the Suśruta-saṃhita is still in preparation.

Vagbhatta Samhita

Vāgbhaṭa (वाग्भट) is one of the most influential writers, scientist, physician and consultant of Ayurveda. Several works are associated with his name as an author, most notably the Ashtāṅgasaṅgraha (अष्टाङ्गासंग्रा) and the Ashtāngahridayasaṃhitā (अष्थाअसाअगरा). However, the best current research argues in detail that the two works cannot be the product of a single author. The whole question of the relationship between these two works and their authorship is very difficult and still has a long way to go. Both works frequently refer to earlier classical works, the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita. Vāgbhaṭa is said in the closing verses of the Ashtānga sangraha to have been the son of Simhagupta and a disciple of Avalokita. His works mention the worship of cows and Brahmins and various Vedic gods, he also begins with a note on how Ayurveda evolved from Brahma. His work contains syncretic elements.

An oft-cited misstatement is that Vāgbhaṭa was an ethnic Kashmiri, based on a misreading of the following remark by the German Indologist Claus Vogel: “..judging from the fact that he expressly defines Andhra and Dravida as the names of two southern nations.” or kingdom, and repeatedly mentions Kashmiri terms for particular plants, he was probably a Northerner and a native of Kashmir…’. Vogel is not talking about Vāgbhaṭ here, but about the commentator Indu.

Vāgbhaṭa was a disciple of Charaka. Both his books were originally written in Sanskrit with 7000 sutras. According to Vāgbhaṭa, 85% of diseases can be cured without a doctor; only 15% of diseases require a doctor.

Sushruta, the “father of surgery” and “father of plastic surgery”, Charaka, the medical genius, and Vāgbhaṭa are considered the “Trinity” of Ayurvedic knowledge, with Vāgbhaṭa coming after the other two. According to some scholars, Vāgbhaṭa lived in Sindh around the sixth century. Not much is known about him personally except that he was most likely a Vedic as he refers to Lord Shiva in his writings and all his sons, grandsons and disciples were Vedic. He is also believed to have been taught Ayurvedic medicine by his father and a Vedic monk named Avalokita.

Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā (Ah, “Heart of Medicine”) is written in poetic language. The Aṣṭāṅgasaṅgraha (As, “Compendium of Medicine”) is a longer and less concise work, containing many parallel passages and extensive prose passages. Ah is written in 7120 easy-to-understand Sanskrit verses that present a coherent account of Ayurvedic knowledge. Ashtanga means “eight components” in Sanskrit and refers to the eight divisions of Ayurveda: internal medicine, surgery, gynecology and pediatrics, rejuvenation therapy, aphrodisiac therapy, toxicology and psychiatry, or spiritual healing, and ENT (ear, nose and throat). There are sections on longevity, personal hygiene, causes of disease, the effect of seasons and time on the human organism, types and classifications of medicine, the importance of taste, pregnancy and possible complications during childbirth, prakriti, individual constitutions and various tools for determining prognosis. There is also detailed information on five-action therapies (Skt. pañcakarma) including therapeutically induced vomiting, the use of laxatives, enemas, complications that may occur during these therapies, and necessary medications. Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā is perhaps the greatest Ayurvedic classic, and copies of the work in manuscript libraries across India and the world outnumber any other medical work. Ah is the central authority of Ayurvedic practitioners in Kerala. In contrast, the Aṣṭāṅgasaṅgraha is poorly represented in the manuscript notation, and only a few partial manuscripts survive into the 21st century. It was evidently not widely read in pre-modern times. Since the twentieth century, however, the As have taken on new significance as they have become part of the curriculum of Ayurvedic higher education in India.

Eight Components

The earliest classical Sanskrit works on Ayurveda describe medicine as divided into eight components (Skt. aṅga). This characteristic of the medical art, “medicine that has eight components” (Skt. cikitsāyām aṣṭāṅgāyāṃ கியியையாம்மும்ஷ்தாதாம்) is found first in Sanc. 4th century BC. The components are:

- Kāyachikitsā: general medicine, body medicine

- Kaumāra-bhṛtya (Pediatrics): Discussion of prenatal and postnatal care of child and mother; methods of conception; the selection of sex, intelligence and constitution of the child; child diseases; and a midwife

- Śalyatantra: surgical techniques and extraction of foreign objects

- Śhālākyatantra: treatment of diseases affecting openings or cavities in the upper body: ears, eyes, nose, mouth, etc.

- Bhūtavidyā: the pacification of possessed spirits and people whose minds are affected by such possession

- Agadatantra/Vishagara-vairodh Tantra (Toxicology): includes epidemics; toxins in animals, vegetables and minerals; and keys to recognizing these anomalies and their antidotes

- Rasāyantantra: rejuvenating and tonic for prolonging life, intellect and strength

- Vājīkaraṇatantra: aphrodisiac; treatments to increase semen volume and viability and sexual pleasure; infertility problems; and spiritual development (transmutation of sexual energy into spiritual energy)

Practice

Ayurvedic practitioners view physical existence, mental existence, and personality as their own unique entities, each element able to influence the others. It is a holistic approach used during diagnosis and therapy and is a fundamental aspect of Ayurveda. Another part of Ayurvedic treatment says that there are channels (srotas) that transport fluids and that the channels can be opened by massage with oils and swedana (stirring). Unhealthy or blocked channels are believed to cause disease.

Diagnosis

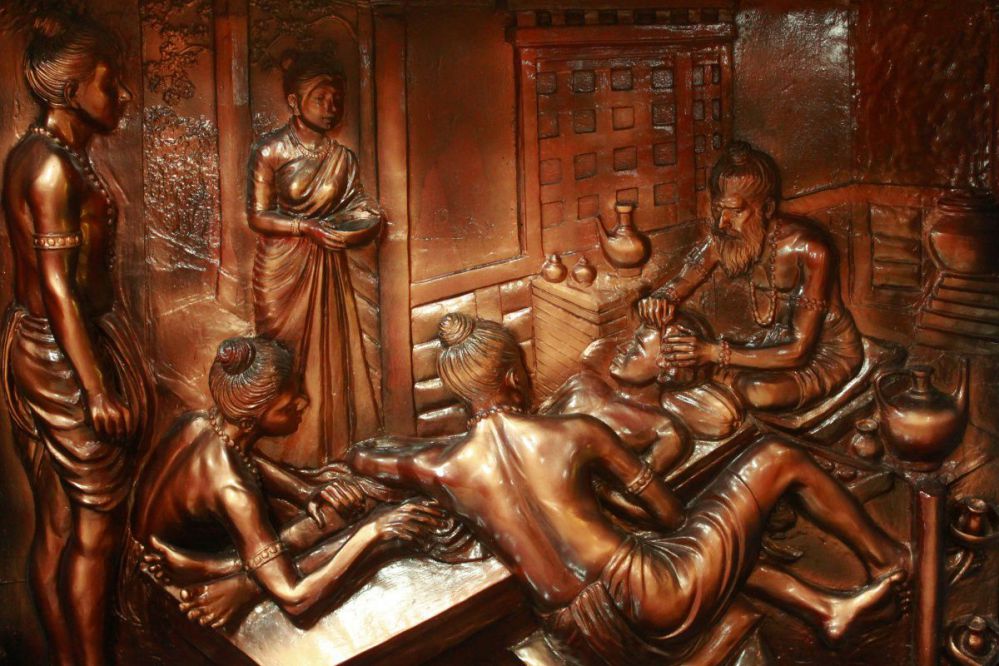

Ayurvedic practitioner applying oil using head massage

Ayurveda has eight ways to diagnose disease, called Nadi (pulse), Mootra (urine), Mala (stool), Jihva (tongue), Shabda (speech), Sparsha (touch), Druk (vision) and Aakruti (appearance). Ayurvedic doctors approach diagnosis using the five senses. For example, hearing serves to observe the state of breathing and speech. The study of the death points or marman marma is of special importance.

Current status

Ayurveda is widely practiced in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, where public institutions offer formal study in the form of Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) degrees. In some parts of the world, the legal status of general practitioners is equivalent to that of conventional medicine. Several scholars have described the contemporary Indian application of Ayurvedic practice as “biomedical” compared to the more “spiritualized” emphasis on the practice found in variants in the West.

Exposure to European developments in medicine from the nineteenth century through the European colonization of India and the subsequent institutionalized support of European forms of medicine among settlers of European heritage in India challenged Ayurveda, challenging its entire epistemology. From the twentieth century, Ayurveda came to be politically, conceptually and commercially dominated by modern biomedicine, leading to “modern Ayurveda” and “global Ayurveda”. Modern Ayurveda is geographically located in the Indian subcontinent and tends towards secularization through the minimization of the magical and mythical aspects of Ayurveda. Global Ayurveda encompasses various forms of practice that have evolved by dispersal to a wide geographical area outside of India. Smith and Wujastyk further state that global Ayurveda includes those primarily interested in the Ayurvedic pharmacopoeia as well as New Age Ayurvedic practitioners (which may combine Ayurveda with yoga and Indian spirituality and/or emphasize preventive practice, mind-body medicine, or Maharishi Ayurveda).